For a commodities market to function properly, three components are absolutely necessary:

Competition

Without sufficient competition, a market will devolve into a monopoly.

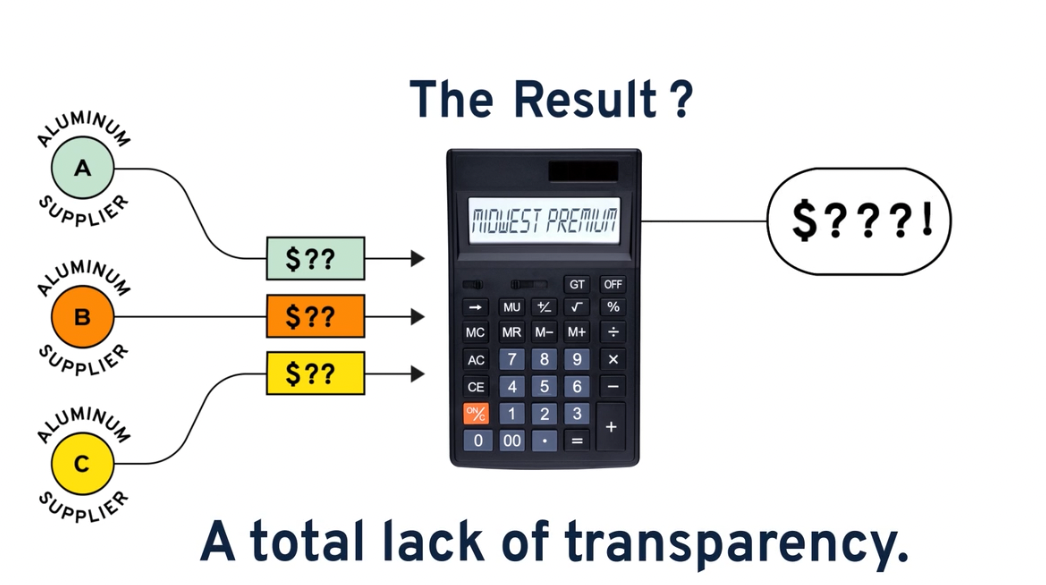

Transparency

Without adequate transparency, consumers have no way of knowing if the price they pay is fair or if it has been arbitrarily manipulated.

Oversight

Without appropriate oversight, markets can be unduly influenced by monopolistic behavior.

Though defenders of the status quo like to claim the Midwest Premium (MWP) is merely an independent assessment of the price of aluminum, the reality is that the MWP is a black box that raises prices for consumers while leaving them in the dark.

FAQ

What can be done to fix this?

Repealing Section 232 tariffs on imported aluminum would provide immediate relief to purchasers of aluminum. Specifically, the APEX Act is a legislative remedy that addresses the problems with the MWP and the U.S. aluminum market:

APEX Act

Increased Midwest Premium Oversight Helps Consumers

Because of the Midwest Premium, companies in the aluminum supply chain charge the full tariffed price on all aluminum, regardless of whether it is subject to tariffs or not, hurting end-users and ultimately consumers.

The MWP has had a significant financial impact on the American beverage industry, which has paid nearly $1.9 billion in taxes since the Section 232 tariffs went into effect. However, of this vast amount, only $126 million (or approximately 7 percent) actually went to the U.S. Treasury. If federal regulators were empowered to increase oversight of how the MWP is benchmarked, there would be increased competition and transparency in U.S. aluminum markets.

With increased transparency in aluminum markets, purchasers would no longer be forced to pay tariffs on aluminum that should not be subject to them and competition would increase.

The result of this process would be lower prices for consumers on goods made with aluminum, such as cans, automobiles and more.